‘It was the most terrifying hour of my life.’

The following was written for the Society of Professional Journalists’ program, Will Write for Food. WWFF13 selected 21 journalists from across the United States to spend 36 hours in a homeless shelter composing a special issue of The Homeless Voice.

I was told I should be afraid of cops.

According to COSAC Homeless Shelter Founder/Director Sean Cononie, police in Hollywood Fla., are cracking down on people who look like me—homeless and asking for a handout.

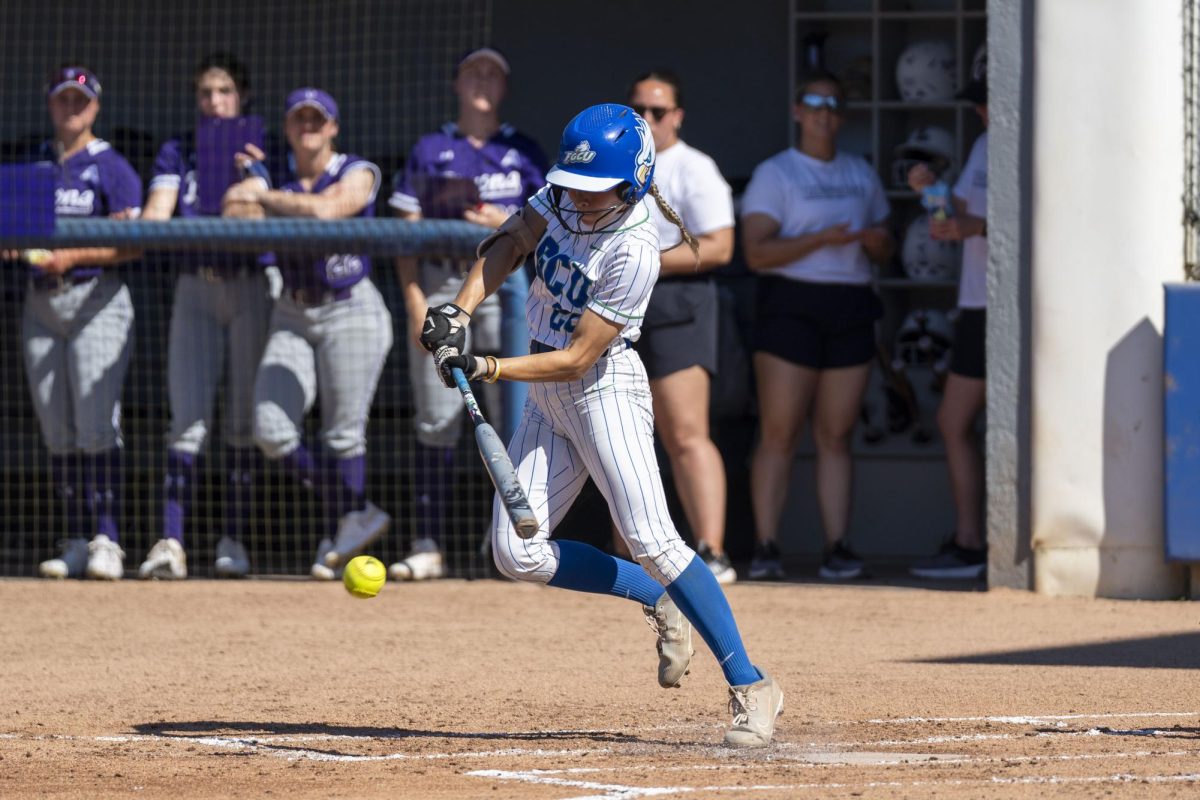

I was covering life at the shelter as part of a reporting project when I decided to pose as a homeless person. I wanted to discover what goes through the mind of a panhandler. To disguise myself I clawed through patches of gravel to bury dirt beneath my nails. I powdered dirt and sand on my right cheek and attempted to mat my hair. COSAC gave me an oversized shirt and khaki pants to wear, but not before wiping them in mud and cutting holes in the legs and sleeves.

I took along a piece of cardboard with HOMELESS scrawled across it in black ballpoint pen. I knew whatever I was able to collect I would donate to COSAC, but I had no idea what to expect once I began panhandling.

In my normal life as a college student, if I’m waiting at a stoplight and see someone holding a scrap of cardboard, I avoid looking at them. I play with the radio or stare at my phone and evade eye contact. I’m not proud of it.

I told myself I would stay on the median for at least one hour. If I could handle staying longer, I would. But any shorter and I felt wouldn’t get the full experience of begging on the street. After 68 minutes I hit my limit.

When I first stepped into the middle of 441 and Sheridan Street, I saw a police car on the side of the road with lights flashing about two blocks away from me. Every few minutes I checked on it to make sure the car hadn’t moved, hoping the officer wasn’t watching for someone like me.

I paced along the thin sliver of median separating the eight lanes of the road – six miles from COSAC.

Another officer drove up to the light a few minutes later and I almost vomited my heart into my mouth. My pulse was roaring in my ears as I prepared an explanation for the officer but each scenario I imagined ended with me in handcuffs. The car was only three lanes from where I stood, so I flipped over my cardboard sign and continued walking, hoping the cop wouldn’t see me.

When the light turned green, he drove away. He didn’t take the time to notice me. I was relieved, but my hands were still shaking.

After that, I started getting some cash.

The first car to stop was in the lane closest to me. The door of a ratty, navy blue sedan cracked open and a man in a green Publix grocery shirt held two $1 bills out for me. I hurried over and took the money.

I felt guilty. This balding, middle-aged man was either on his way to or from work, where he made less money in an hour at a grocery store than I did panhandling. I took two perfectly crisp dollar bills from him. Still, I was glad it had been so easy.

I had no time to enjoy my first donation because a big, sweaty man began walking up and down the road about 70 feet from me. I assumed he was a veteran panhandler.

He paced the streets as cars whizzed past. Eventually he took off his shirt, as the sun beat down onto his shinning head and bulging gut. I worried he was going to tell me I was on his corner.

For a split second, I was annoyed he was taking over my territory. Then I realized how dumb that sounded. My annoyance morphed back into terror and I turned my attention back to traffic.

Most people passing by refused to give me money. A few did. They shrugged their shoulders, said, “good luck,” and were gone once the light turned green. I had never felt someone pity me before, but I could see sympathy in their eyes.

I hated that. I would rather they ignore me than look at me with those eyes.

After 30 minutes, a guy with a Creole accent pulled up in a meticulously clean black jeep. He waved at me and I trotted over to his rolled-down window. He looked me up and down, and then began to fish through his wallet. “Why do you need to do this?” he asked, nodding to the tattered cardboard sign in my hand. “You’re so beautiful. You don’t have any family?”

“No,” I lied.

Then he asked me if I had a boyfriend and my heart began to slam against my chest again. I thought he might try to proposition me and I wanted the light to change so this guy would give me his money and leave.

“Why aren’t you in school?” he said as I walked away.

“Thank you,” I said as the light finally turned green.

I had only been homeless for 30 minutes and I already didn’t trust anyone around me. I felt disconnected from people I would usually consider harmless. Honest questions, such as the one the Creole man had asked, were too probing. The more people talked to me, the more I wanted them to go away.

I became grateful for the people who ignored me. I knew I wouldn’t have to worry about them trying to squeeze information out of me. I suddenly felt less guilty for avoiding eye contact with the panhandlers I had driven past.

After 68 minutes I stopped. My fear was too intense. In an hour, I had collected $32 and a loaf of multigrain bread.

It was the most money I’ve ever made in an hour.

People think panhandling is easy. I did. After all, it’s just asking for money. But having to beg for cash — to have people either look at you as a stain on society or completely ignore you — was one of the most upsetting situations I’ve ever put myself in. Not because it was humiliating, as I had assumed it would be, but because I mistrusted everyone around me — and even feared them — because I felt as if my value was somehow less.

Back at the shelter, I gave the cash to COSAC, but first I gave the loaf of bread to a resident named Judith who couldn’t eat much because she kept kosher. A huge grin spread on her sun-wrinkled face and she hugged me with gratitude.

That night, at three in the morning, I sat on the floor of my shower and let the warm water wash the sweat and grime of the day off me. I had never been so grateful for soap and water, but the memories of that hour didn’t wash away.

Those 68 minutes have become a part of me.

Geoffrey Stephens • Oct 1, 2013 at 3:30 pm

Beyond the creative efforts and ideas for this piece, it was a terribly broad generalization of what it is to be homeless.

So much so that, having been homeless myself for years on and off, it was insulting. Did I have “dirt buried beneath my nails” and “dirt and sand on my face?” No. Did I carry a piece of cardboard with me? No. Does everyone who is homeless panhandle? No. For the almost mugshot-like photo of Kalhan “being homeless” did she have make-up on or make sure her hair looked okay? Yes.

If the take on being homeless is that of dirt beneath the nails and smeared on one’s face then the poor panhandler likely doesn’t have eye-liner.

Even though stated that just over an hour posing like this would encompass “the full experience,” then this is the furthest and most ridiculous assumption and display of being homeless I literally have ever seen or read. I feel Kalhan’s feelings of guilt more likely stemmed from the fact that this piece was hardly skimming the surface of the true reality and done more for show.

Students feel guilt or shame in just walking alone on campus without a smartphone to look down at, or headphones in their ears. Guilt or shame as stated in the piece is the most superficial and predictable notion to come from homelessness.

I applaud the efforts to even take some action at all involving one’s self, but was again insulted and sickened by the “buttering up” of things for affect playing onto the superficial looks of someone who is homeless and/or a panhandler and their emotions. Many homeless people that I both met and interacted with when being homeless are actually fairly well kept. When someone goes homeless this does not automatically make them some dirty buffoon who can’t think critically or resourcefully and have their looks about them.

Like myself and my means when faced with this situation, I know how others and I would use public restrooms or say a public park or beach shower unit to wash up regularly. At one point I even offered a fellow homeless guy my other Mc D’s cheeseburger when full, only to be denied by him stating he was a vegetarian.

The only credit I can give to this piece is that of a super-opinionated one, of which then takes flight upon what a homeless character would appear to be like in a Disney movie.