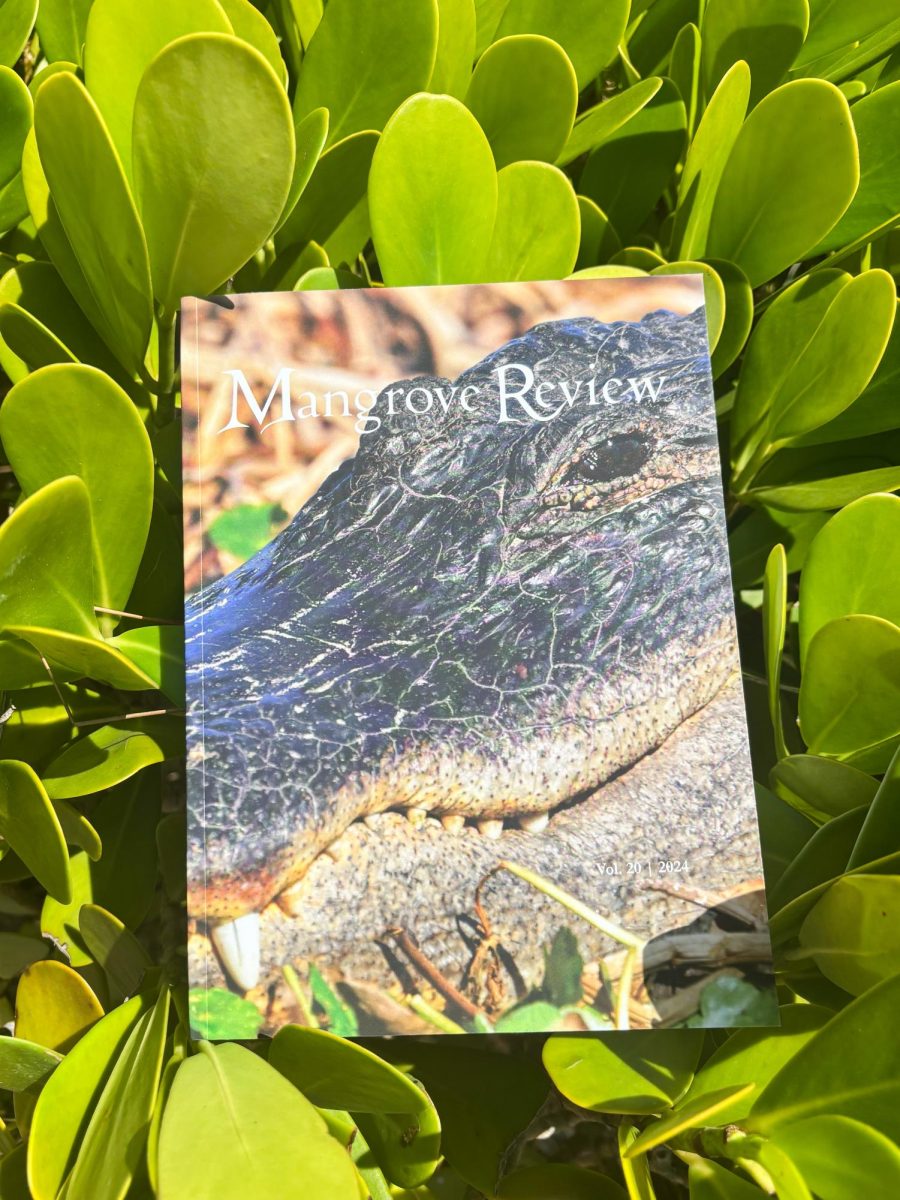

When attending a school nestled in more than 400 acres of preserved wetlands and uplands, it is not uncommon to find wildlife roaming the main campus.

John Herman, an FGCU biology professor who was called to remove a 4-foot alligator out of the South Village pool a few weeks ago, says that the school’s wildlife is not a nuisance, but a perk of living in a location that the school is in.

“I want [students] to appreciate and observe, but not have any direct interaction with the wildlife,” Herman said. “We have a big group of new freshmen coming in and we have a ton of wildlife on this campus and it’s not just out in the conservation areas. It’s everywhere.”

Earlier this summer, students spotted a bear on FGCU Boulevard en route to their 8 a.m. classes. The bear disappeared back into the woods and hasn’t been seen since.

Wildlife such as turkey, alligators, hogs, bald eagles, red-shouldered hawks, indigo snakes, gopher tortoises, armadillos,raccoons, white-tailed deer, opossums and even an occasional panther or bear can be found on campus simply because those are the organisms that live in the surrounding areas.

Although students are not given any written material about the wildlife on campus or living with wildlife, it is mentioned during campus tours.

“It’s something that the orientation leaders go over during their tours,” said program coordinator Tabitha Dawes. “It’s not something we give them as a hard copy, but we do mention it to them. If we had that resource, we’d be more than willing to include that into the documents new students receive during orientation.”

FGCU Wings of Hope Panther Posse Program Director Ricky Pires recently passed out information to resident assistants that explained what should be done in the situation of a student finding an injured animal. Pires is currently working to wildlife-proof garbage cans around campus with the impending construction of the new road from South Village Loop to Ben Hill Griffin Boulevard.

“We’re developing so much around the university and it’s going to be taking more resources away from our wildlife,” Pires said. “When that happens, they come looking for food.”

Herman, whose main focus is herpetology, along with Pires, who teaches conservation and living with wildlife to Environmental Humanities students though Wings of Hope, want to create a new system of dealing with wildlife that is the safest possible for not only the students, but the animal(s) involved as well.

Pires calls the unofficial committee the “Critter Couriers.”

“We want to develop an actual university committee that can make this a policy and act as advisors for situations like this.” Herman said. “For now, it’s an unwritten policy.”

When University Police receives a wildlife call, UPD responds to the area to evaluate the situation and make sure to avoid and student/animal interactions.

“Depending on the animal, there’s a variety of ways ” said UPD Chief Steven Moore. “It’s mainly keeping the people back and allowing the animal to do what it needs to do.”

In the case of the pool-hopping alligator, according to Herman, if he or any other FGCU “courier” weren’t called, UPD would’ve called Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. When FWC has what they consider a nuisance alligator, they call a trapper. However, when trappers are called, the gator is usually terminated.

“We work with whoever,” Moore said. “It’s a team effort. We generally don’t have any real problems, the animals take care of themselves, whether it’s alligators, snakes or anything else. We just kind of ‘shoo’ them back into the woods or ponds.”

Moore emphasized that students should not be trying to handle the animal or feed it.

“We just want everyone to be safe,” Moore said. “In the case of say a gator on campus, we have to make sure to keep the students back. When they surround the gator, it will just sort of freeze up and stay there.”

So far this year, UPD has received 36 wildlife calls. Since 2012, there have been a total of 156 calls ranging from alligators to deer to bears.

“Whether they call us or not is up to them, we’re trying to make it a policy,” Herman said. “I think for now, UPD using on-campus resources and faculty to deal with these calls is a good first step.”

Herman says that although it is important to take safety into consideration, it’s not always necessary to call UPD when wildlife is spotted.

“Students are going to run into stuff that may make them feel uneasy, especially if they’re using the nature trails, and that’s OK,” Herman said. “Appreciate it and leave it be. Every time you see wildlife, you don’t have to call the police. If you think there is an issue, call them, but otherwise, leave it alone. There’s no reason to act on it or over react. It’s cool to see these things, that’s what makes this campus so unique.”

Living with wildlife on campus

The Florida Alligator – It is against Florida law to feed an alligator. When a gator is fed, FWC is forced to put down the gator for fear of it associating humans with food. If it poses an immediate threat, call UPD.

The Florida Black Bear – It is against Florida law to feed a bear, especially by leaving out trash and unfinished food. When a bear is fed, FWC is forced to put down the bear for fear of it associating humans with food and teaching their young to do so as well. If it poses an immediate threat, call UPD.

Snakes – Leave them alone. There is no reason to kill a snake or approach a snake, especially if it is venomous. If it poses an immediate threat, call UPD.