“Where are our vigils?” a student asked the lecture hall of fellow students and university representatives. Her question rang out, but no one had an answer for her.

Pulse had a vigil, she said. 9/11 had a vigil. But, where is the campus vigil for black shooting victims?

Minority student organizations at FGCU hosted an open forum Tuesday night to discuss the topics of racial profiling and victim blaming nationally as well as white and black disconnect on campus. The forum was petitioned in light of recent shootings of black men in Tulsa, Oklahoma and Charlotte, North Carolina.

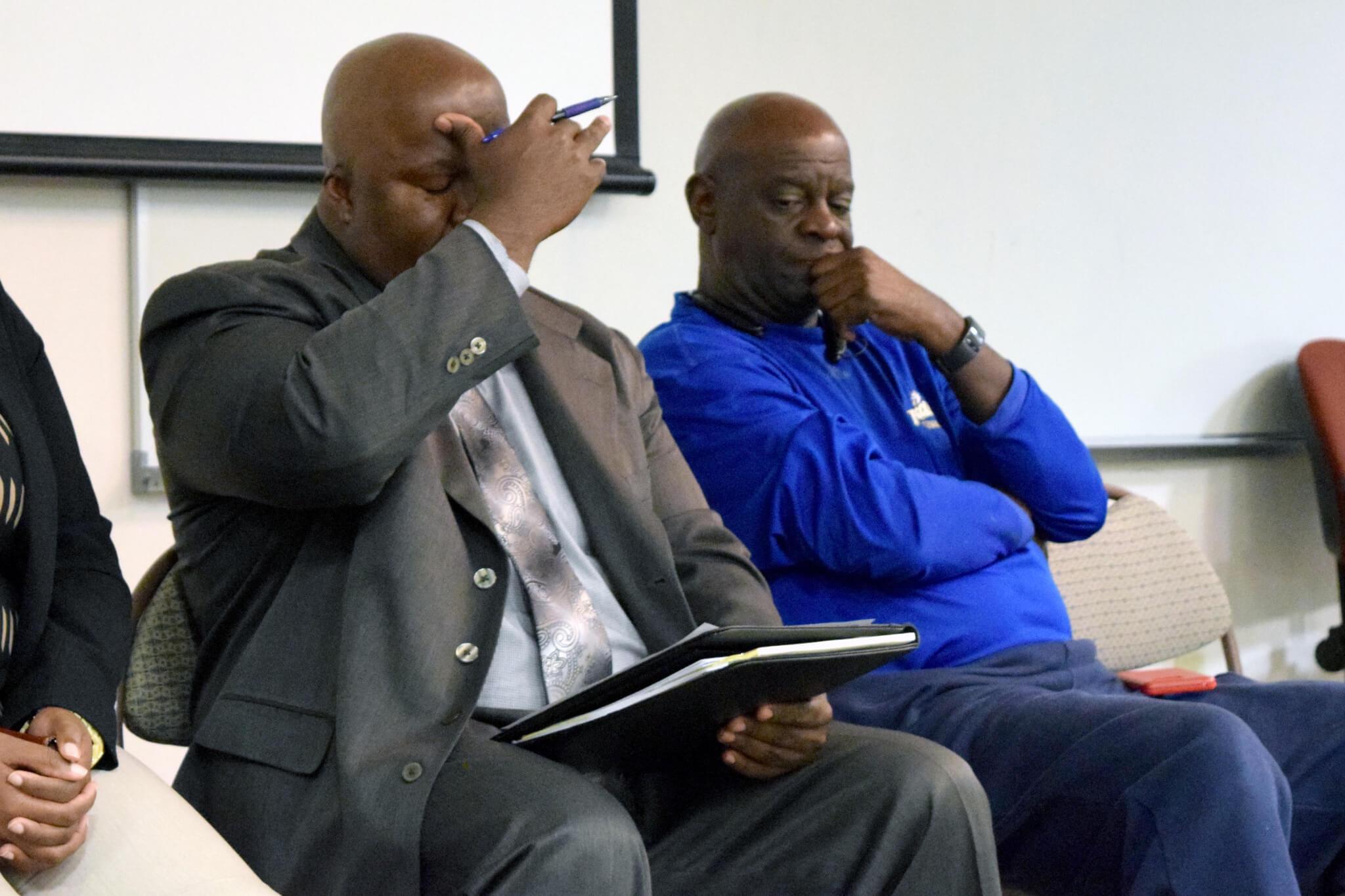

The six-person panel was moderated by Dyonne Bergeron, the director of the office of Multicultural and Leadership Development at FGCU.

“This has been going on for a long time. Some of the things that have been happening have brought me to tears. I look out at all of you,” Bergeron said to the 50-person crowd, “and I don’t want to see you on the news.”

The panel included representation from every corner of campus, including J. Webb Horton, the assistant director of community outreach; Tony Barringer, the associate provost for Academic Affairs; Precious Gunter, the assitant director of the Office of Institutional Equality and Compliance; Anthony Hyatt, the senior coordinator for community outreach; Jameson Moschella, the associate director of residence education; and Brandon Washington, the IEC director.

Representatives from Counseling and Psychological Services as well as Housing and Residence Life were also in the crowd along with Rhema Bland, the student media advisor; Julie Gleason, the assistant dean of students; and Michele Yovanovich, the dean of students.

Even with the large number of university representatives, the discussion was led in majority by students in the crowd, the majority of which were black — an issue that was raised throughout the night.

Jeremy Burke-Ingram, the president Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., shared the story of his most recent encounter with police. It was a routine stop he said, but he said he felt terrified.

“I was so careful to do exactly as the officer said,” Burke-Ingram said. “I didn’t want to give myself the chance to be one of those hashtags.”

Burke-Ingram referred to the recent popularity of hashtags in memory of black shooting victims, a topic that came up again and again throughout the two-hour forum.

“Would we even know about these shootings had it not been for these hashtags, for social media?” said Sadia Zama of Muslim Student Association. “This isn’t new. The world is just hearing about it now.”

Nuniez Philor, an FGCU student, shared his experience growing up in adjacent Naples.

“Growing up there, it’s true; there wasn’t the same racial tensions that exist elsewhere,” Philor said. “But, this means my white friends from there have this mindset watching what’s happening in the news that it can’t be happening, that racism doesn’t exist if they aren’t witnessing it themselves.”

Panel member Tony Barringer, the associate provost for Academic Affairs, spoke from his background in law enforcement on how he believes the nation can resolve the tension between the criminal justice system and the black community, saying the black community’s distrust must be dissolved and law enforcement training must be improved.

In response, Malik Hines, the president of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity and leader in the Student African American Brotherhood mentoring program, addressed media’s role in the issue of racial tension in the U.S.

“The media victim-blames,” Hines said. “First, it was ‘why was he wearing a hoodie?’ or ‘why was he out that late?’ Now, we have our hands up, in broad daylight, and we’re still being shot and killed. But, what can I do? I can’t not be black.”

Ashakeen Sterling, the president of Black Student Alliance, also put the blame on media for unequal coverage of white and black shooting victims.

“Victims are not being treated as a victim; police are,” Sterling said. “The cop had a reason to kill him simply because he had a prior arrest? Now, I have to tell my significant other, if we ever get pulled over, I’m getting my phone out. I don’t know if the next time we’re pulled over will be the last time.”

Several women in the crowd followed with similar stories of fear for their significant others each time they walked out the door.

Students also addressed the recent term “black-on-black crime,” which some have used to state that more black men are killed by other black men than by white law enforcement.

“The thing is, that statistic is true of every race and ethnicity,” said Brandon Washington, the Title IX coordinator. “Majority of white people are killed by white people. Most Hispanics are killed by Hispanics. We only see this statistic used against blacks though.”

Jameson Moschella, the sole non-minority on the panel, spoke candidly and apologetically on the subject.

“These implicit biases exist because, frankly, white people don’t know black people,” Moschella sad. “How many of us, as white people, have really taken the time to intimately get to know black people — spend time with them so we can understand what’s going on? Where is the room of white students who are allies for our black students?”

Washington said the biggest hurdle in creating these types of relationships is white society’s “microaggressions” toward the black community. A common microagression the black community specifically faces is being told they “aren’t like other black people” or “are basically white.”

“You see, most racism is racism of omission rather than racism by commission,” Washington said. “It’s somebody sitting across the room rather than next to you.”

Precious Gunter, the deputy Title IX coordinator, said she faced the barrier of microaggressions in her prior field of law, which is disproportionately white, but soon saw that she was changing people’s views by working hard and proving their misconceptions wrong. Microagressions are intentional or unintentional dismissive statements made to people of color based upon their race or ethnicity.

“Every time you wake up in your beautiful, black skin and come to campus and interact with others,” Gunter said to the crowd, “you change the stereotypes people have about you and the black community.”