An agar plate lies still. Omnicron has destroyed the layer of bacteria inside the plate, leaving plaques or dark holes 2 mm in diameter. Omnicron is a virus replicating itself inside the plate. The discovery of this virus belongs to Tasha Baer, a Florida Gulf Coast University student from the 2013-14 Virus Hunters course. Baer’s discovery of a virus is not the only one. Fourteen of her classmates join the discovery of unique viruses.

Each student like Baer isolates, names and analyzes new mycobacteriophages (known as phages) or viruses that infects one or more of the mycobacteria (bacteria) that are inside the plate. FGCU students have sequenced two viruses that refer to the process of ordering how the subunits in a chain of a virus are structured. The results among other information about the viruses are on the Mycobacteriophage Database (phagesdb.org), which is a national database that collects and shares data, pictures and related information.

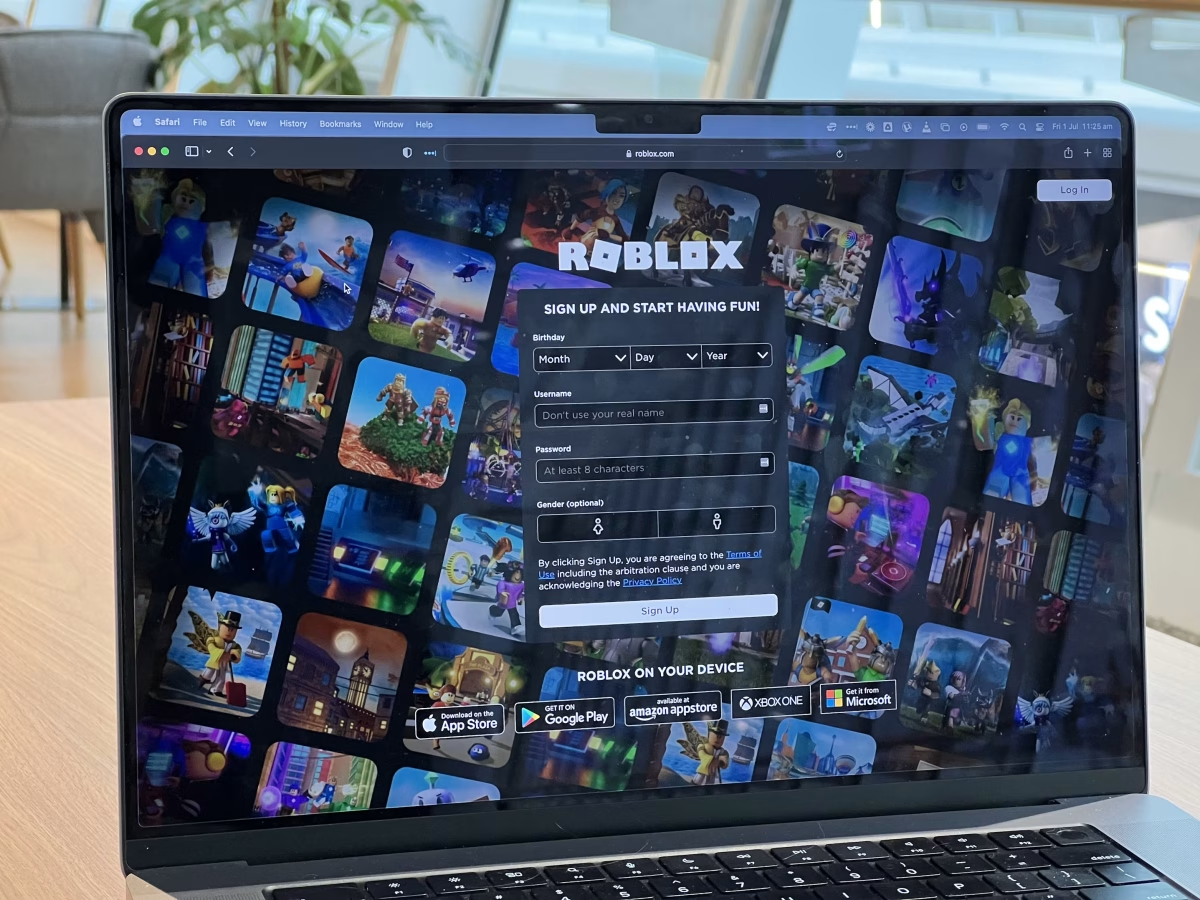

This opportunity for students comes with approval from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Science Education Alliance–Phage Hunters Advancing Genomics and Evolutionary Science program. The SEA-PHAGES program encourages students to join the research-based laboratory course to discover and learn about the new phages. After a competitive process last year, eight schools, including FGCU, are members, and FGCU is now moving forward on its second year, joining over 70 schools in the U.S.

Each student or virus hunter who takes the honors class at FGCU is not researching alone. From last year’s roster, seven are now teaching assistants. One is a former TA and the rest are students from the 2013 honors virus hunters class. These teaching assistants or “phage masters” help the 19 students and Sharon Isern, Ph.D. before, during and after this year’s class.

The class involves rigorous training before students can even begin to “hunt” for viruses.

Necessary techniques. Mandatory sterilization. Soil sampling. Research. Here’s an inside look at what students learn during the first and second semester:

First semester:

Virus discovery

“I had no idea what I was doing,” said Samantha Gatt, a first-year student who took the class through dual enrollment and is now a teaching assistant. “This time I finally realized what everything meant.”

Virus hunters begin learning techniques using instruments such as micropipettors of P1000, P20 and others to transfer volumes. The micropipettors lay on the table that the phage masters prepare before class.

The hunters will only need to come and sterilize the equipment and table before use.

“There is a lot of behind the scenes stuff,” said Santiago Yori, a second-year student. “You have to set up everything.”

“When you start getting closer to the end, that’s when it becomes very important, and you’re working with drops that you can barely see, so you have no clue if you actually did anything,” said Brandon Ashley, another TA.

Experience working with instruments varies for each student as well; knowing the instruments will allow students to move forward in their research.

Even though the viruses are not harmful to people, fungus contamination can be a result inside the plate if the student’s bacteria from their surroundings or themselves falls inside the plate, creating other bacteria.

“Students need to protect the bacteria from us,” Isern said.

After learning the techniques and appropriately sterilizing the tools, each student collects a soil sample from anywhere they choose as long as they record the GPS coordinate. Next, they isolate a virus from the other billion virus particles from the sample. The students will eventually find one virus, or a pure or homogenous preparation of that virus that replicates itself.

Isern’s trip with her 14 students last year to the University of Florida allowed the students to see their viruses face-to-face using the electron microscope. Before that, students prepare their samples on

grids with a drop of liquid with a virus inside and properly stained on a grid.

After the visit, students name their viruses. A criteria is in place for students to follow and a committee of scientists approves the name.

The University of Pittsburgh keeps a sample of the viruses in a repository.

Following a material transfer agreement, any scientist can study the virus.

After the discovery, these hunters now share a database with their virus in place.

“You [students] have added to the body of knowledge that is helpful to others,” Isern said and added that it’s not over. After the first semester, students will enter a competitive process inside the class to send one virus to a sequence facility for its genome. Last year, HHMI paid the sequence for Omnicron.

Second semester:

Comparative analysis

The hunters begin the second semester by annotating the sequence of Omnicron using computer databases, and using the computer databases is new for some students.

“I [have] had biology labs before, but I’ve never done biology work on a computer before,” Yori said.

Yori adds, “I’m in a huge learning curve right now.”

As a first-year phage master, he is also a student who did not attend the first semester class; however, he may help guide students through the sequence research the following semester. The familiar process to Yori will show the hunters what is the function of the virus’ individual gene, what is its structural gene, among other things. The computer will tell the hunters if it is a gene, and they will do an “open reading frame.” Basically, they will compare the data to known, national databases, and the research will let the hunters know if the gene is in other discovered organisms or viruses.

After learning about the virus’ sequence, students will move forward to independent research projects. In teams of two students per group, they further characterize the virus.

The hunters will then work on his or her poster about their viruses, and everyone presents during Research Day at FGCU. Students can also compete in the Life Sciences South Florida STEM Undergraduate Research Symposium. Two students from the class will represent the school by attending and presenting at the annual symposiwum during the summer. With the teacher’s feedback, the students elect the speakers. Last year’s FGCU representatives were Taylor Power and Yori.

One student already plans to attend and present at the annual symposium. As a senior this year, Stephanie Fine said she would not have been in the class if the email from advising did not reach her inbox.

“I want in,” Fine said when she heard about the course from Yori.

“I’m a senior, but I don’t know much about viruses,” said Fine, who is reaching closer to graduation to become a professional scientist.

Perhaps opportunities for the class members spread like a virus, because something new is underway at FGCU.

To understand the biodiversity of the viruses that affect bacteria, HHMI is asking 12 schools around the country to develop and pilot a protocol and try experimenting with different bacterial hosts with the virus HHMI provides. FGCU is one of those schools.

HHMI has also chosen four faculty members nationwide to train two newly accepted cohort schools into the program this 2014 summer. Isern and Scott Michael, Ph.D, are two of those faculty facilitators.

Categories:

One student gets to name lab discovery

August 27, 2014

Story continues below advertisement

0

More to Discover