By Julia Bonavita

Photography Editor / Contributing Writer

The negative stigma only children are faced with is based solely on misinformation and the inability to fathom growing up without siblings. Often perceived as spoiled, antisocial, or even entitled, kids without siblings are faced with a unique challenge — one where they are expected to debunk these misconceptions without falling to the typical stereotype.

A person’s family life should not be judged based on how many people they share parents with, but instead factor in a multitude of variables such as income, parental marital status and other key factors involved in raising a child.

In May 2019, The New York Times published an essay titled “My Marriage Has a Third Wheel: Our Child” as part of an ongoing series where parents delve into the trials and tribulations of raising children. Throughout the piece, author Jancee Dunn paints a surprisingly negative picture of her small family, and further solidifies many stereotypes surrounding only children. Dunn described her child as being “insulted” if she and her husband went out for dinner alone.

After reading this article, I did the only thing I knew how to do: Took to Facebook to air my grievances. My long-winded and uncharacteristically confrontational comment earned over 1,000 reactions online, and I was contacted by a New York Times reporter regarding my take. My heart hurt for the author’s daughter, because I too understood what it felt like when your parents are also your closest companions. Although my response was laced with personal anecdotes and emotion, it got me thinking — why are only children subjected to so much hate?

A 2016 study conducted by Jiang Qiu, a professor of psychology at Southwest University in Chongqing, China and published by Forbes Magazine found that only children scored higher than participants with siblings in “flexibility”, which is believed to be linked to how creative a person is. Researchers also found that only children scored the same when compared to those with siblings when tested on traits such as intelligence, extraversion and openness.

The majority of recent studies involving only children suggest there are no major personality differences between those with or without siblings, yet we are often ridiculed for our perceived “privilege”. Throughout my lifetime, my admittance of being an only child has either been met with surprise at how I “don’t act like one” or automatic assumptions that I’m vain and antisocial.

Being an only child, or “oneling” as Dunn puts it, comes with a unique upbringing. Those with siblings are often surprised when they relate to what only children experience, further solidifying that the two lifestyles really are not that different.

I was taught the fundamentals on how to share my things, but only had to when my friends were over. I learned about privacy, boundaries, and the idea that my things were “mine” at a young age, which allowed me to treat my friends with the same values, and not encroach on their toys and shared items.

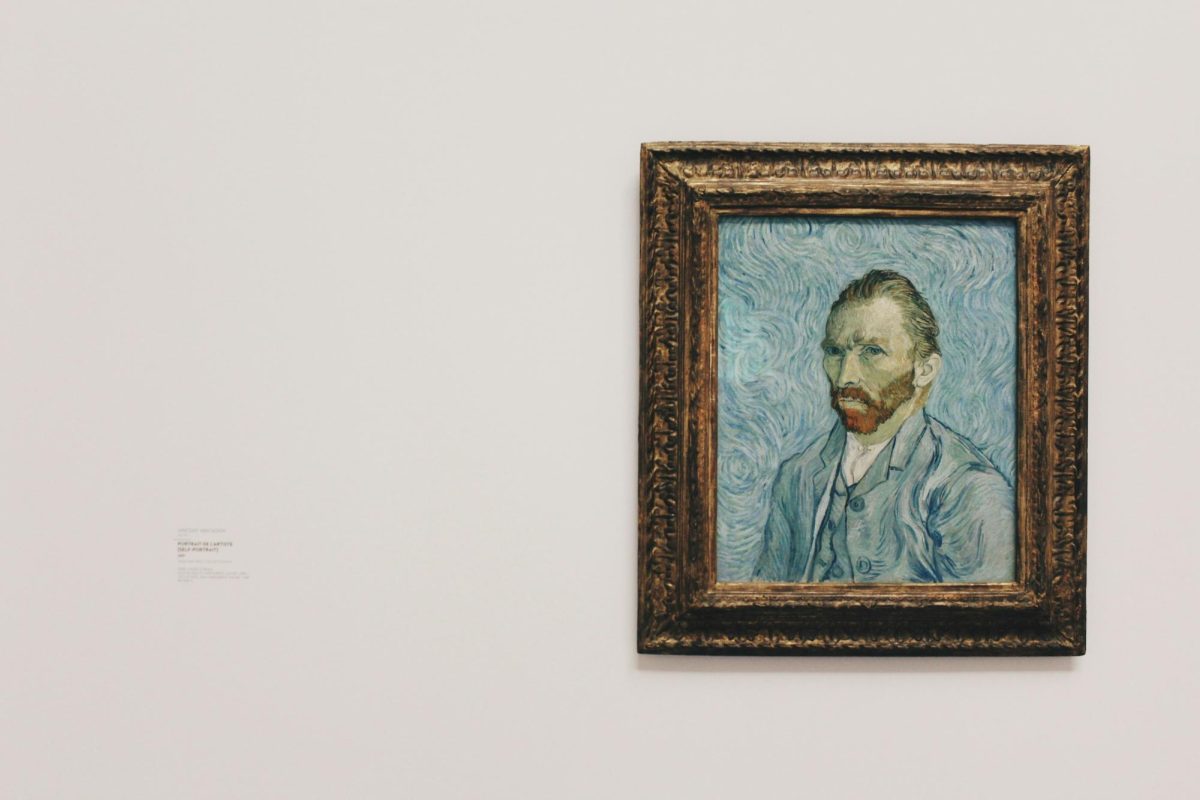

Christmas morning included handwritten letters from Santa Claus, personalized wrapping paper and my dad’s camcorder pointed directly at me — but when all the presents were unwrapped and my mom was preparing dinner, I had to learn how to play with my new toys by myself. My mind was bursting with creativity and imagination, but often unwilling to waiver in the way I chose to do things.

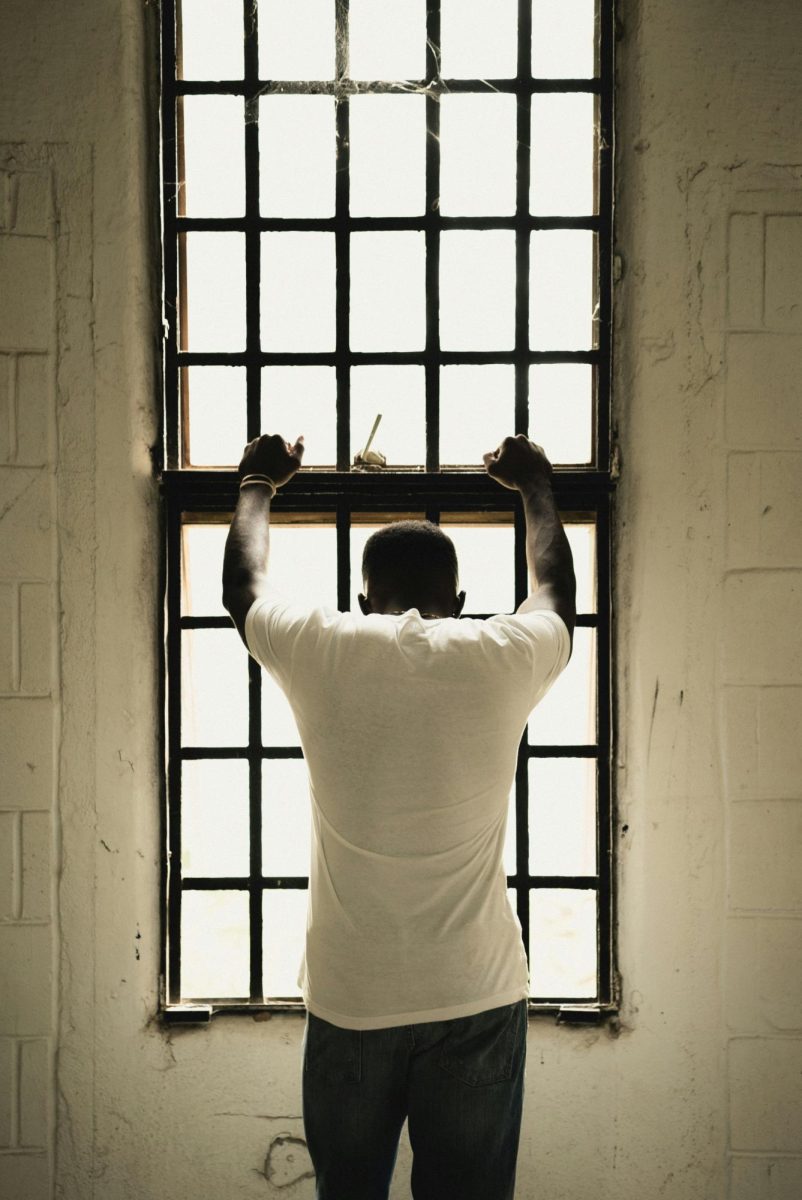

Growing up without siblings also posed many challenges, many of which would not apply to a family with multiple children. When the time came for my friends to leave our playdates, I was left to entertain myself. Interactions with people my age were limited to school and scheduled get-togethers, and I became oddly well-versed in speaking “adult”. My nine-year-old self preferred to sit with the grown-ups, because that was what I was accustomed to.

My entire life was put under a microscope, because my parents were able to focus all their energy towards me. I was expected to include my friends’ name, address, phone number, parent’s occupation, and specific event details each time I asked my parents if I could go out. I continue to obey my midnight curfew at age 20, and was required to electronically sign a contractual agreement before I was allowed to take my car to college. I was subjected to an intense list of rules and expectations, similar to those of the oldest sibling, because I was their first child and therefore the “guinea pig”.

However, the constant attention was often helpful. My parents encouraged me through every college application, and I received one-on-one driving lessons. They were always at every school function and performance, and made sure I arrived at every extracurricular activity, doctors appointment, and playdate on time.

Moving into a college dorm was difficult. I went from having an entire side of the house to being expected to share a bathroom, kitchen and living area with three roommates, who often complained that I kept the place “too clean” as I was careful to not leave any evidence of my existence. I had to learn how to cohabitate with people my own age, and took extra precautions so I would not annoy them.

My parents often took the “two-against-one” approach, and I was often tasked with trying to win over one parent in order to get what I wanted. I never had a sibling in my corner to argue with my parents about what movie we would watch or if we’d go out for ice cream, but I became an incredible salesman.

The brain chemistry of only children differs from those with siblings. The same study released by Qiu showed a significant difference in the supramarginal gyrus, the portion of the brain that is associated with management, planning and flexibility, and medial prefrontal cortex, which involves emotional regulation and agreeableness. Therefore concluding that only children excel in creativity, may struggle with agreeableness and do not differ in IQ development when compared to children with siblings.

I’m sure my parents would argue that I too am the third wheel in their marriage. I’ve been present at every anniversary dinner and will admit I still get jealous when they send me photos of their travels while I’m away at school. But unlike Dunn, they have never suggested that my presence is a burden on their relationship. Parents of only children also take on a unique role: They are their child’s primary caretaker, playmate and the majority of their human interaction. My parents were constantly tasked with balancing their family duties and engaging in activities that most siblings would do.

Jancee Dunn put a face to the hate surrounding only children. Her daughter, like every other “oneling”, is expected to adapt to managing a personal life with her peers when her main social interaction takes place with primarily adults.

My parents’ choice to have one child does not reflect on my core values persona. The generalized assumption that only children are “spoiled” and “privileged” is entirely misguided, and based solely on false stereotypes. Only children are simply misunderstood, and only ask to be treated similarly to those with siblings. Every family dynamic is different, and although size is an important factor, it is not the sole component that decides how a child will fare in the world.

Amanda • Apr 12, 2022 at 8:05 am

Thank you for this. I have always loved being an only child. People rarely believe me when I say I never wanted siblings, but I truly never did. My childhood was happy, busy, and full of love. I now am raising an only child with an only child partner and I wouldn’t have it any other way. The only area I struggle with is the need for people to constantly comment on our family size.

Alene Makrush • Mar 18, 2021 at 9:10 am

I found your article very fascinating and interesting. I am the baby of my family, with three older siblings as well as a twin. In the article, you mentioned that an only child may struggle with agreeableness. I think that this is where a lot of the stereotypes of only children being “spoiled” or “privileged” comes from. A kid with no siblings probably does not have the constant forced interaction with other people of varying ages. In school, the only child interacts with kids their age. In a family, especially a large one, the child interacts with siblings who are1, 2 or 3 years younger or older. Anyways, it is no surprise that an only child tends to score lower on agreeableness. Based on my own experiences, an only child does tend to be more “my way or the high way” type of personality. In a group project, an only child tends to push their own ideas without yielding to differing ideas from their peers. This type of behavior is especially noticeable at a younger age, but not so much as a teen or an adult. I hope this all makes sense!